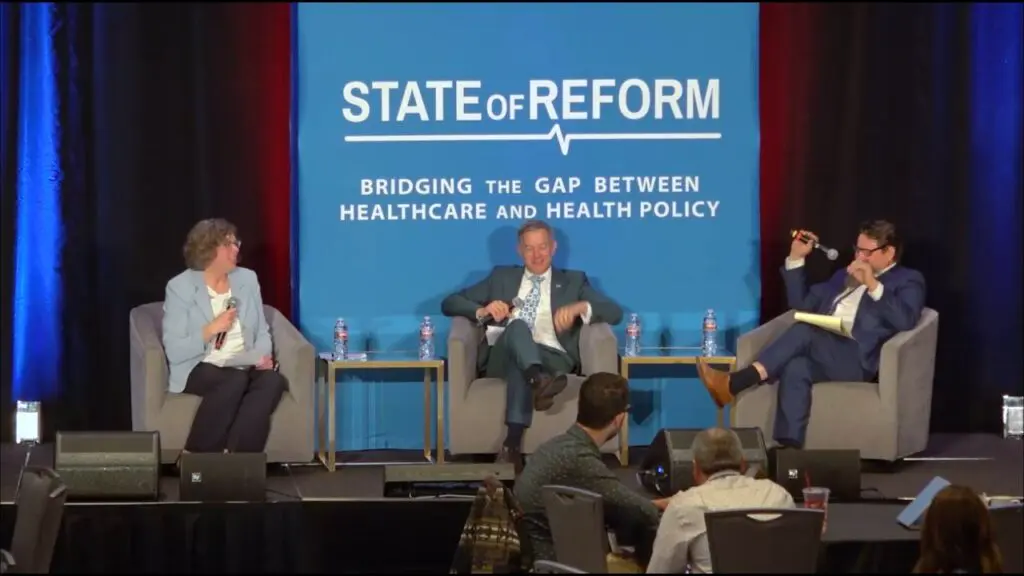

There’s nothing like it–hearing directly from the people running the systems and doing the work … and to understand what the unique challenges are here, and really help the state facilitate progress. – Oregon health policy consulting executive

This conference offers something really important in the overall discourse of healthcare reform. It really comes down to the gap between policy and the actual tools that are available and being used on the ground in order to fulfill the needs of the patients and the provider teams that are offering these services. – Florida health IT leader

I attend the Utah State of Reform Conference every year. The thing that I love most is all of the people who come, who I know and who I don’t know, and I get an opportunity to network with them and talk with them—share thoughts and ideas and build something together that, moving forward, is something very tangible. – Utah health system executive

It gives us all a forum to come together, discuss the critical issues, and it really prepares us to just advocate for the things that we all share a common interest in. – Hawaii health plan CEO

We really appreciate that State of Reform brings together all sorts of disparate groups to have healthy dialogue. They can break out into different sessions that really interest them. It’s a really great space for we health policy nerds to [discuss] where our next steps need to go. – Washington Medicaid director

Just as important as the keynote speakers and the breakout sessions is the networking that happens behind the scenes. – Colorado health policy consultant

There’s nothing like it–hearing directly from the people running the systems and doing the work … and to understand what the unique challenges are here, and really help the state facilitate progress. – Oregon health policy consulting executive

This conference offers something really important in the overall discourse of healthcare reform. It really comes down to the gap between policy and the actual tools that are available and being used on the ground in order to fulfill the needs of the patients and the provider teams that are offering these services. – Florida health IT leader